Art has always reflected society’s hidden tensions, and few subjects have been as quietly radical as the portrayal of sex workers in contemporary galleries. For decades, their images were either erased, eroticized, or reduced to stereotypes-mysterious figures in shadowy alleys, or tragic victims with no names. But in the last 20 years, something shifted. Sex workers began to speak for themselves-not through the brush of a male painter, but through their own cameras, performances, and installations. This isn’t just about representation. It’s about reclaiming identity.

Some artists turned to documentary-style work, filming real conversations with sex workers in cities like London, Berlin, and Bangkok. One such project, filmed in 2022, followed an escort girl in uk over six months as she navigated client interactions, legal gray zones, and the loneliness that comes with invisibility. Her voice, unedited and raw, became the soundtrack to a gallery exhibit titled Not Just a Service. The piece didn’t ask for pity. It asked for recognition. If you want to understand the lived reality behind the term, uk glamour girl escort isn’t just a marketing phrase-it’s a label that carries weight, risk, and resilience.

The Body as Canvas, Not a Commodity

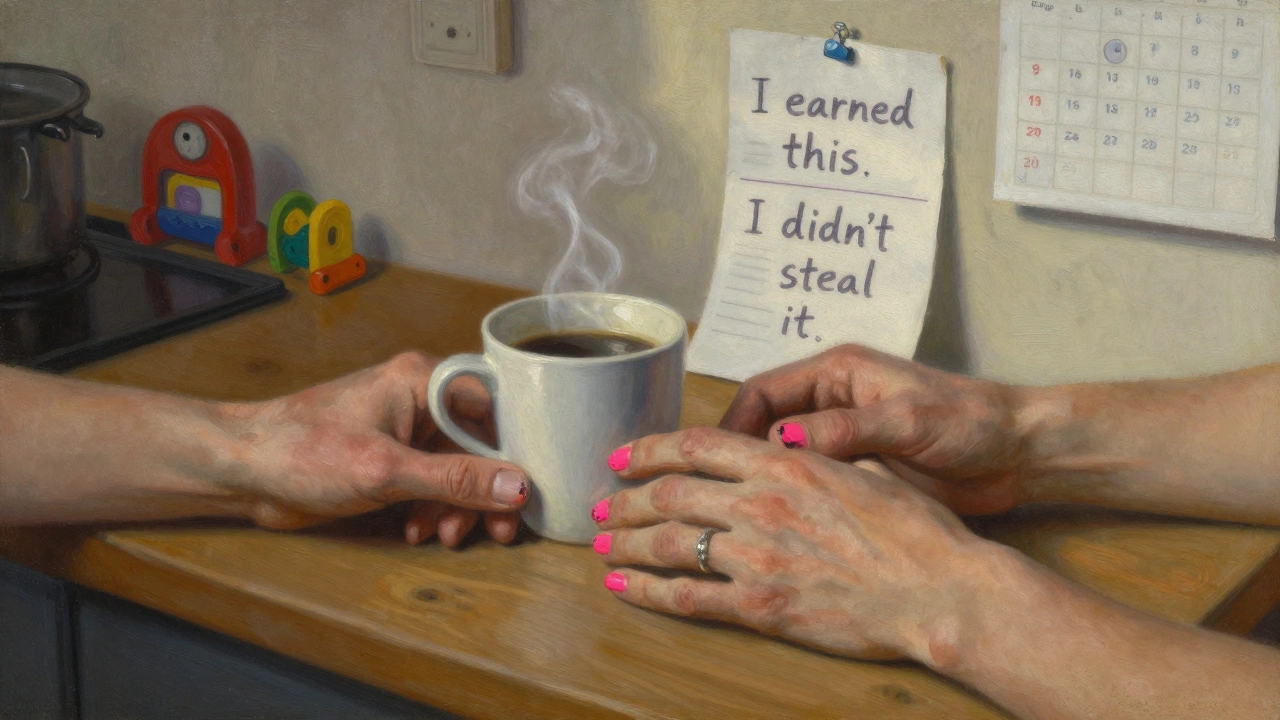

Contemporary artists are rejecting the idea that sex work is inherently exploitative. Instead, many are showing it as labor-complex, negotiated, and sometimes empowering. In 2023, artist Mira Chen held a solo show in New York called Hourly Rate. Each painting was based on a real client interaction, but instead of depicting the clients, she painted the sex worker’s hands-the only part visible in every scene. Calloused fingers holding a coffee cup. Nails painted in chipped neon pink. A wedding ring worn on the right hand, not the left. These details told stories no headline ever could.

The work sparked debate. Critics called it voyeuristic. Others called it revolutionary. What made it powerful was that Chen didn’t use models. She collaborated directly with sex workers, paying them as co-creators. One participant, a former nurse turned independent worker in Manchester, said, “They think we’re broken. But we’re just people who chose a different way to pay rent.”

From Marginal to Mainstream

The art world has slowly opened its doors. In 2024, the Tate Modern included a piece by activist-artist Jules Rivera in its permanent collection: a 12-minute video loop titled Client List. It plays on a loop in a dimly lit room. The screen shows a woman typing out client requests on a laptop, then deleting them. One by one. Over and over. The audio is her voice reading each request aloud-“I want you to pretend you’re my ex,” “Can you wear the red dress?” “I just need someone to talk to.”

No faces. No bodies. Just words. And silence. The piece was purchased after a public campaign led by sex worker collectives. It wasn’t bought because it was beautiful. It was bought because it was uncomfortable. And that’s the point.

Challenging the Law Through Art

Legal restrictions shape how sex work is seen-and how it’s shown. In the UK, while selling sex isn’t illegal, many related activities are: soliciting in public, running a brothel, or even sharing a flat with another worker. These laws force sex work underground, making it harder to document, harder to organize, and harder to portray in art without fear.

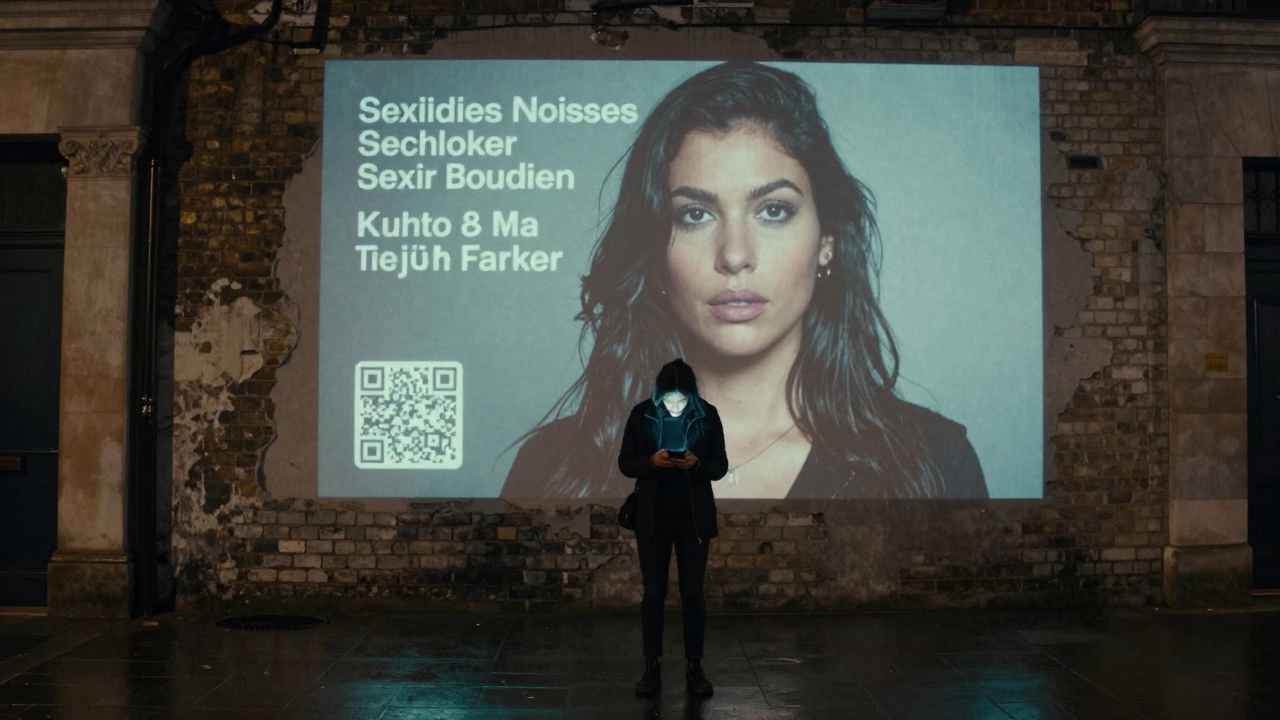

Artists are pushing back. In 2025, a collective called Decrim Now launched an outdoor projection series in London’s Shoreditch. At night, the walls of abandoned buildings lit up with portraits of sex workers-real names, real faces, real addresses. Each image came with a QR code linking to a voice recording where the person spoke about their daily life, their fears, their dreams. One woman, a single mother working part-time as a uk escort girl, said: “I don’t want to be a symbol. I want to be seen as a person who’s trying to get by.”

Why This Matters Beyond the Gallery

These artworks aren’t just for art lovers. They’re tools for change. Studies from the London School of Economics show that public perception of sex workers improves significantly after exposure to firsthand narratives-especially when those narratives come from the people themselves. Art creates empathy where statistics fail.

When a museum hangs a painting of a sex worker’s hands, it says: “This person’s labor matters.” When a film festival screens a video made by a trans sex worker in Glasgow, it says: “Your story belongs here.” When a billboard in Birmingham displays the face of a woman who was arrested for working from home, it says: “This is not a crime. This is survival.”

The Next Wave: Art as Activism

The most powerful work today isn’t hanging on walls. It’s happening in TikTok livestreams, Instagram stories, and community zines. Younger artists are bypassing galleries entirely. They’re using social media to share their own art-photographs of their apartments, selfies with client receipts blurred out, handwritten letters to their younger selves.

One artist, known only as “Luna,” posts weekly on Instagram. Her posts show her cooking, reading poetry, walking her dog. Sometimes she captions them with: “This is what I do when I’m not working. I’m not a fantasy. I’m a person.” Her following has grown to over 200,000. Not because she’s glamorous. But because she’s real.

There’s no single definition of what this art is. It’s not protest. It’s not pornography. It’s not tragedy. It’s documentation. It’s testimony. It’s the quiet refusal to be erased.

What’s Missing?

Despite progress, gaps remain. Most of the art still centers white, cisgender women. The voices of Black, Indigenous, migrant, and non-binary sex workers are still underrepresented. Artists of color often struggle to get funding. Galleries still prefer “safe” narratives-those that fit neatly into liberal narratives of victimhood or empowerment.

There’s also a lack of institutional support. Very few art schools offer courses on sex work as a subject. No major university in the UK has a research center dedicated to the art of sex workers. And when exhibitions do happen, they’re often temporary, poorly funded, and rarely reviewed by mainstream critics.

But change is coming. A new initiative called Art & Autonomy, launched in late 2024, is training sex workers in photography, video editing, and curating. So far, 17 participants have shown work in pop-up galleries across the UK. One of them, a 34-year-old mother from Leeds, had her piece selected for the Liverpool Biennial. Her work? A series of selfies taken in her kitchen, each with a different receipt taped to the wall behind her. The caption reads: “I earned this. I didn’t steal it.”

The art isn’t asking for permission. It’s already here.